|

|

|

|

Today's Labor Movement Needs a Bigger Vision

It is time for the labor movement to use its organization and resources to fight to stop this wave of repression. As part of that effort, labor needs to propose a freedom agenda for immigrants that will really give people rights and an equal status with other workers on the job, and their neighbors in their own communities. Photo: David Bacon

[This article is part of a Labor Notes roundtable series: How Can Unions Defend Worker Power Against Trump 2.0? We will be publishing more contributions here and in our magazine in the months ahead. Click here to read the rest of the series.—Editors]

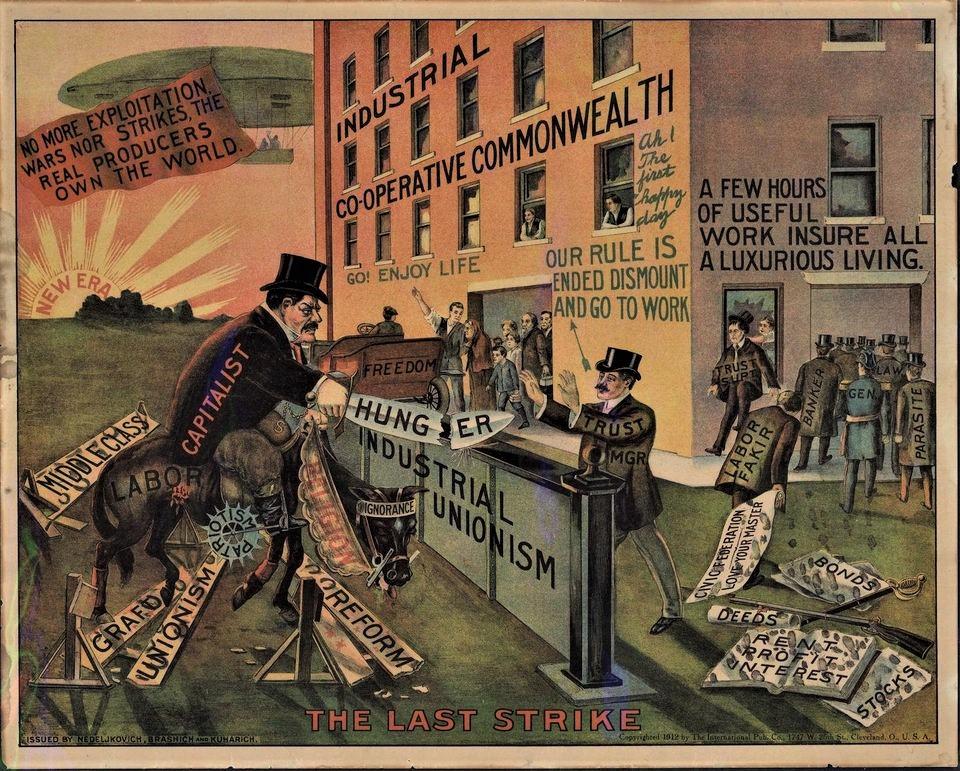

During the Cold War, many of the people with a radical vision of the world were driven out of our labor movement. Today, as unions search for answers about how to begin growing again, and regain the power workers need to defend themselves, the question of social vision has become very important. What is our vision in labor? What are the issues that we confront today that form a more radical vision for our era?

The labor movement needs a freedom agenda. When Zohran Mamdani spoke after his primary election victory in New York City, he declared, "We can be free and we can be fed." Mamdani is telling our unions and workers that we can reject the old politics of agreeing to war abroad and repression at home, in the hopes that at least some workers will gain.

PEACE ECONOMY

We don't have to go back to the CIO and the radicalism of the 1930s to find voices in labor calling for a radical break from the past.

In the 1980s, while Reagan was President, William Winpisinger, president of the Machinists, told his members, thousands of whom worked in arms plants, that they would gain more from peace than from war. Under union pressure in 1992, Congress even passed a bill calling for redirecting a small part of military spending into conversion for a peacetime economy.

One big part of that program is peace. Another is reordering our economic priorities.

Right now working class people have to fight just to stay in the cities. They’re being driven out, and this has a disproportionate impact on workers of color. Unions and central labor councils need to look at economic development, and issues of housing and job creation. That would start to give us something we lack, a compelling vision.

IMMIGRANT RIGHTS

Since 2006 millions of people have gone into the streets on May Day. The marches in 2006 were the largest outpourings since the 1930s, when our modern labor movement was born. In one of the best things our labor movement has done, we began raising the expectations of immigrants when we passed the resolution in Los Angeles in 1999 changing labor’s position on immigration.

We put forward a radical new program: amnesty, ending employer sanctions, reunification of families, protecting the rights of all people, especially the right to organize. That came as a result of an upsurge of organizing among immigrant workers themselves, and support from unions ranging from the United Electrical Workers to the Carpenters.

Congress, however, has since moved to criminalize work and migration, and proposed huge guest worker programs. States have passed bills that are even worse.

Mississippi, for instance, made it a state felony for an undocumented worker to hold a job, with prison terms of up to ten years. Florida has made it a crime to give an undocumented person a ride to a hospital. And administrations from Bush to Trump have implemented by executive order the enforcement and guest worker measures they couldn’t get through Congress.

LABOR’S SILENCE

When Democrats campaigned against Trump by accusing him of sabotaging an immigration bill that would have put billions of dollars into immigration enforcement, they prepared the way for Trump's onslaught once he was elected. Labor, which should have prepared our own members for the fight to come, stayed silent.

In the wave of raids that have followed, hundreds of our own members have been taken, not just for deportation, but on bogus criminal charges or simply swept off the streets by masked agents. Unorganized workers have been terrorized by the raids—a gift to employers as workers are pressured to give up any hope of a union or a higher wage.

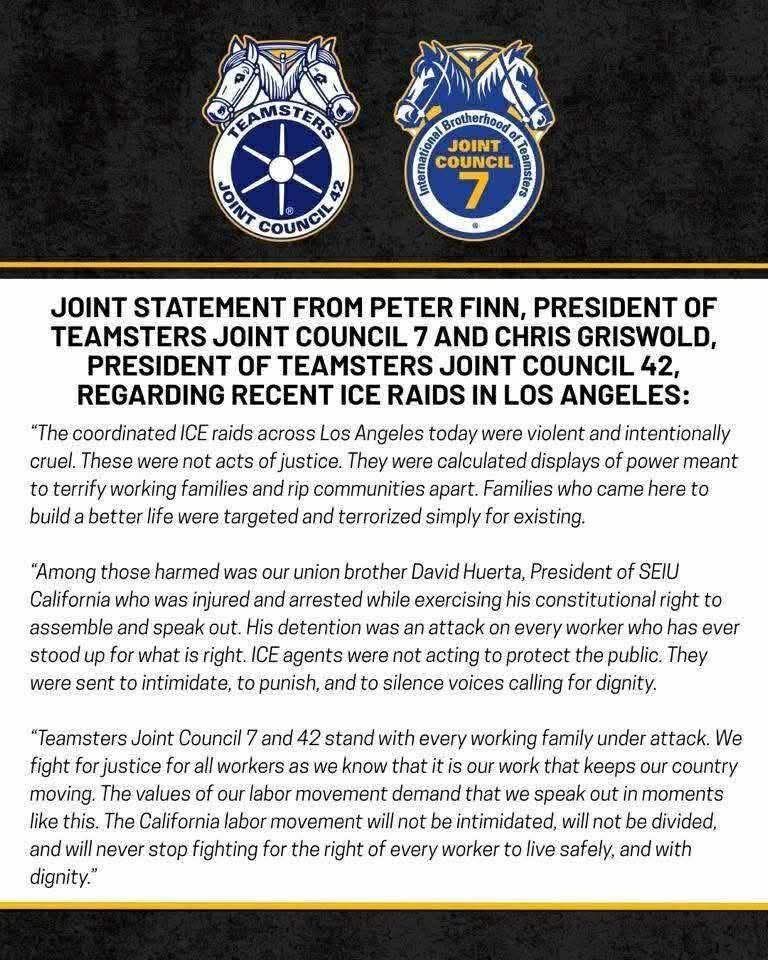

Some unions today are part of the network fighting to protect workers and communities from immigration raids. SEIU California leader David Huerta faces misdemeanor federal charges after opposing ICE during a raid in Los Angeles' garment district.

It is time for the labor movement to use its organization and resources to fight to stop this wave of repression. As part of that effort, labor needs to propose a freedom agenda for immigrants that will really give people rights and an equal status with other workers on the job, and their neighbors in their own communities.

DEFEND CIVIL RIGHTS

In the past, the possibility of fighting for our ideals—what we really want—has been undermined by beltway deal making. We have to be consistent in our politics.

Labor needs an outspoken policy that defends the civil rights of all sections of U.S. society, and is willing to take on an open fight to protect them. If Trump's raids and terror campaigns scare unions into silence, few workers will feel confident in risking their jobs (and freedom) to join them.

Yet people far beyond unions will defend labor rights if they are part of a broader civil rights agenda, and if the labor movement is willing to go to bat with community organizations for it.

JOBS FOR ALL

A new direction on civil rights requires linking immigrant rights to a real jobs program and full employment economy. It demands affirmative action that can come to grips with the devastation in communities of color, especially African-American communities.

And none of that can be done without challenging Trump's war policies, but equally the war policies that have come from Democratic administrations.

CLIMATE JUSTICE

Today part of a freedom agenda is not only conversion from military production, but conversion from fossil fuel dependence.

Jeff Johnson, past president of the Washington State Labor Council, drew the connection between labor support for climate conversion legislation and social justice. "I knew we had to educate my members, so that they would understand that we can't support more fossil fuel exploration," he told me. "We have an existential crisis that is social, political and racial, in addition to climate. And we know that the impact of climate change will hit those communities who had the least to do with causing it."

INTERNATIONAL SOLIDARITY

At the heart of any radical vision for our era is globalization—the way unions approach the operation of capitalism on an international scale.

When the old Cold War leadership of the AFL-CIO was defeated in 1996, I heard incoming AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer (later President) Richard Trumka say unions should find partners in other countries in order to face common employers. At the time it represented a big change—that unions would cooperate with anyone willing to fight against our common employers. It rejected by implication the anti-communist ideology that put us on the side of employers and U.S. foreign policy, and that shamed us before the world.

Three decades later, however, this idea is no longer radical enough.

It’s an example of pragmatic solidarity, although it was, at the time, a

good first step out of that Cold

War past.

What’s missing is a response from the labor movement to U.S. foreign policy. International solidarity involves more than multinational corporations. There is no doubt that military corporations benefit from selling the bombs that Israel uses in its Gaza genocide, but political support from Trump, and Biden before him, for Israel is more than just an effort to defend their profits.

Corporate globalization and military intervention are intertwined, and in the labor movement there’s not enough discussion about their relationship. That’s why we got manipulated in the response to 9/11, and by justifications for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

WHICH SIDE ARE YOU ON?

Unions in the rest of the world are not simply asking us whether we will stand with them against General Electric, General Motors, or Mitsubishi. They want to know: Will you take action to oppose the Gaza genocide and arms shipments? What is your stand about aggressive wars or coups?

U.S. corporations operating in a country like Mexico or El Salvador are, in some ways, opportunistic. They’re taking advantage of an existing economic system, and trying to make it function to produce profits. They exploit the difference in wages from country to country for instance, and require concessions from governments for setting up factories in their countries.

But what causes poverty in a country like El Salvador? What drives a worker into a factory that, in the United States, we call a sweatshop? What role does U.S. policy play in creating that system of poverty?

In our union movement, we need that kind of discussion. We turn education into simply a technical matter about techniques for grievance-handling and collective bargaining. We don’t really work with our members to develop a framework to answer these questions. So our movement becomes ineffective in fighting about the issues of war and peace, globalization, and their consequences, like immigration.

EDUCATE THE MEMBERS

When the AFL-CIO campaigned in Washington against the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), for instance, labor lobbyists went up to Capitol Hill and tried to mobilize pressure on Congress to defeat it. But what was missing was education at the base of the labor movement.

Had we educated and mobilized our members against the Contra war and the counterinsurgency wars in El Salvador and Guatemala (and certainly many of us tried to do that), U.S. workers would have understood CAFTA more clearly a decade later.

The root of this problem is a kind of American pragmatism that disparages education. We need to demand more from those who make the decisions and control the purse strings in our unions.

Since grinding poverty in much of the world is an incentive for moving production, defending the standard of living of workers around the world is as necessary as defending our own. The logic of inclusion in a global labor movement must apply as much to a worker in Mexico as it does to the nonunion worker down the street.

That’s why the debate over the Iraq War at the AFL-CIO convention was so important. From the point when it became clear that the Bush administration intended to invade Iraq, union activists began organizing a national network to oppose it through U.S. Labor Against the War. What started as a collection of small groups, in a handful of unions, became a coalition of unions representing over a million members, the product of grassroots action at the bottom of the U.S. labor movement, not a directive from the top.

That experience was put to work when the genocide began in Gaza, as national and local unions and activists organized the National Labor Network for a Ceasefire. When the United Auto Workers endorsed its call, the union also set up a divestment and just transition working group, "to study the history of Israel and Palestine, the union’s economic ties to the conflict, and to explore how to achieve a just transition for U.S. workers from war to peace."

Opposing intervention and war means fighting for the self-interest of our members. It means being able to identify that self-interest with the interest of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. The same money that pays for bombs for the Israeli government is money that doesn’t get spent on schools here at home. We can’t have a full-employment economy in the U.S. without peace.

The arguments by political centrists in the Democratic Party that we must choose to fight only about workers' immediate economic interests, and stay silent about Gaza or racism, hides the connections workers have to make to challenge the sources of their own poverty and the attacks against them. As veteran organizer Stewart Acuff says, "While economic justice must run through everything our movement does, we cannot deemphasize any strand of injustice."

Union members are not ignorant of this basic fact. In fact, they are becoming more sophisticated, and better at understanding the way global issues, from war to trade, affect the lives of people in the streets of U.S. cities. But the percentage of union members is declining, and the organization they need to put that understanding into practice is getting smaller. Deeper political awareness alone will not create a larger labor movement.

NEED A SOCIAL MOVEMENT

Just after World War II , unions represented 35 percent of U.S. workers. It’s no coincidence that the McCarthy years when the Cold War came to dominate the politics of unions was the moment when that strength began to decline.

By 1975, after the Vietnam War, union membership had dropped to 26 percent. Today only 9.9 percent of all workers, and 5.9 percent in the private sector, are union members.

Declining numbers translate into a decline in political power and economic leverage. California (with one-sixth of all union members) and New York (with one-eighth) have higher union density than any others. But even there, labor is facing an all-out war for political survival.

While the percentage of organized workers has declined, unions have made important progress in finding alternative strategic ideas to the old business unionism. If these ideas are developed and extended, they provide an important base for making unions stronger and embedding them more deeply in working-class communities. But it’s a huge job. Raising the percentage of organized workers in the United States from just 10 to 11 percent would mean organizing over a million people. Only a social movement can organize people on this scale.

In addition to examining structural reforms that can make unions more effective and concentrate their power, the labor movement needs a program that will inspire people to organize on their own, one which is unafraid to put forward radical demands, and rejects the constant argument that any proposal that can't get through Congress is not worth fighting for.

A BROADER VISION

The labor movement has to become a movement that inspires people with a broader vision of social justice. Our standard of living is declining. Workers often have to choose between paying their rent or their mortgage or having health care. There’s something fundamentally wrong with the priorities of this society, and unions have to be courageous enough to say it.

Working families need a decent wage, but they also need the promise of a better world. For as long as we’ve had unions, workers have shown they’ll struggle for the future of their children and their communities, even when their own future seems in doubt. But it takes a radical social vision to inspire the wave of commitment, idealism, and activity.

The 1920s were filled with company unions, the violence of strikebreakers, and a lack of legal rights for workers. A decade later, those obstacles were swept away.

An upsurge of millions in the 1930s, radicalized by the Depression and left-wing activism, forced (relative) corporate acceptance of the labor movement for the first time in the country's history.

There are changes taking place in our unions and communities that can be the beginning of something as large and profound. If they are, then the obstacles unions face today can become historical relics as quickly as did those of an earlier era.

David Bacon is a labor journalist and photographer, author of Illegal People: How Globalization Creates Migration and Criminalizes Immigrants and other books.

|

| |

|

The missing piece in the Senate committee hearing on the challenges facing newly unionized workers

Earlier this month, the Republican-led U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) notably held a hearing on labor law reform that sought to both identify problems workers face when they seek to unionize and explore possible solutions.

A major focus of the hearing was Senator Josh Hawley’s (R-Mo.) Faster Labor Contracts Act—bipartisan legislation to improve the process for reaching initial collective bargaining agreements when workers first organize a union. Currently, it is a common tactic for employers to slow-walk the bargaining process because there are no penalties for doing so, and delay frustrates workers and undermines their union. Research shows that only 36% of newly organized bargaining units achieve an initial collective bargaining agreement within a year, and a third of newly organized bargaining units still do not have a first contract after three years.

The Faster Labor Contracts Act would require parties to begin bargaining promptly after a union is certified, and if bargaining fails to produce an agreement within 90 days (or longer if the parties agree), the parties would be required to engage in mediation. If mediation was not successful, an arbitration panel would be convened to hear from both parties and render a final and binding decision on the terms of an initial collective bargaining agreement. Through this process, workers would be assured of reaching an initial collective bargaining agreement—the reason they sought to organize a union—within a reasonable period of time.

Addressing the first contract problem is a vitally important part of the labor law reform discussion, but it is only one piece of the puzzle—it will not fix our outdated, failed labor law and provide a real opportunity to unionize for the millions of non-union workers who want a union. Senator Hawley’s Faster Labor Contracts Act is pulled directly from the more comprehensive Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act. The PRO Act would not only provide first contract mediation and arbitration but also rein in employer interference in the election process, establish monetary penalties for violations of the National Labor Relations Act, and override state “right-to-work” laws, among other reforms.

Curiously, there was no mention in the HELP Committee hearing of how the Trump administration is already undermining what the Faster Labor Contracts Act aims to do. The legislation relies on the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service (FMCS) to provide the mediation and arbitration services that are at the heart of the legislation. But President Trump has tried to shutter the agency and the agency has only survived because of two lawsuits against the Trump administration to stop the agency’s closure. Scores of experienced mediators have left the agency, and FMCS has eliminated many of its services and limited the number and type of mediations it will do in its diminished state. President Trump’s budget again proposes to shutter FMCS—he has proposed only enough money to close the agency down permanently in his FY 2026 budget.

Without a robust, government-supported mediation and arbitration system, the Faster Labor Contracts Act would not be able to live up to its promise. It is no answer to say that employers and unions can hire mediators and arbitrators in the private market. While there are many excellent mediators and arbitrators in the private market, the cost can often be prohibitive, with fees that often run into thousands of dollars per day of services.

Nor should the parties have to foot the bill on their own. Since 1935, our federal policy has been explicitly to “encourage[e] the practice and procedure of collective bargaining.” Congress established the FMCS in 1947 to assist employers, workers, and unions in the collective bargaining process in furtherance of this policy and to promote industrial peace. Over the years, FMCS has provided important services at no cost to the parties, including early intervention in new collective bargaining relationships and training on the collective bargaining process along with mediation and dispute resolution services. Before the Trump administration essentially shut them down, FMCS helped reach first collective bargaining agreements at the first unionized Apple Store and at the National Institutes of Health, among others. All of these services are vital to supporting the collective bargaining process and furthering our national policy in support of collective bargaining.

Of course, FMCS’s operations could be improved—that’s the case with every agency, business, and organization. And the agency has suffered from the lack of a Senate-confirmed director for years. But the bottom line remains that if we are to offer a genuine solution to the first contract problem, an independent agency to assist the parties in the collective bargaining process must be restored.

|

|

|

Starbucks to close underperforming stores in restructuring efforts

Starbucks says it will close underperforming stores across North America as CEO Brian Niccol pushes ahead on a company restructuring effort, which is expected to cost $1bn in a bid to revive the company’s flagging sales.

The coffee chain announced the decision on Thursday.

Overall, store count in the United States and Canada is expected to drop by 1 percent, or several hundred stores, by the end of the 2025 fiscal year, including its iconic Seattle roastery.

Niccol is trying to restore the chain’s “coffeehouse” feel to bring customers back to its outlets after six consecutive quarters of declining US sales.

The cuts are expected to affect 900 workers and follow 1,100 corporate cuts earlier this year. But the cuts are underscored by Niccol’s compensation package valued at $95.8m last year, 6,666 times more than the average barista. It is the largest CEO-to-worker pay gap of any company in the S&P 500, according to the Institute for Policy Studies’ 2025 executive excess report.

Unionized stores hit

Among the closed stores was Starbucks’s flagship unionised location in Seattle, a large cafe with an in-house roastery, the company confirmed.

Talks between Starbucks and the Workers United union, which represents more than 12,000 baristas, began last April, but have hit a wall since.

In December, some members of the union walked off their jobs in multiple US cities in a strike that spanned several days during the peak holiday season.

Workers at the Seattle store, which is located near its headquarters, voted to unionise in 2022, and the union picketed the store on Monday over contract negotiation disputes.

A unionized store in Chicago, on Ridge Avenue, was also closed, the union confirmed. Baristas at the store were picketing on Thursday morning, in a plan made before the store’s closure was known, the union said.

Baristas on the picket line came from stores across the Chicago area. “We’re here to remind the company that it’s the workers who actually bring the people into the stores,” said Diego Franco, who came from a store in the Chicago suburb of Des Plaines.

A Starbucks spokesperson said the union status of stores was “not a factor in the decision-making process.”

In a statement, Starbucks Workers United criticised the closures. “It has never been more clear why baristas at Starbucks need the backing of a union,” the union said, adding that it planned to bargain for affected workers so they could be transferred to other stores.

Analysts at TD Cowen estimate that about 500 North American company-owned stores were affected by the restructuring.

Talks between Starbucks and the Workers United union, which represents more than 12,000 baristas, began last April, but have hit a wall since [File: Matt York/AP Photo]

A revamp attempt

In his first year on the job, Niccol has zeroed in on investing in Starbucks’s stores to reduce service times and restore a coffee-house environment, while also trimming management layers.

The company has posted a string of quarterly sales declines in the US as demand for its pricey lattes took a hit from consumers turning picky and competition ramping up.

“During the review, we identified coffeehouses where we’re unable to create the physical environment our customers and partners expect, or where we don’t see a path to financial performance, and these locations will be closed,” Niccol said in a letter to employees.

The CEO said the company would end the fiscal year with nearly 18,300 total Starbucks locations – company-operated and licensed – across the US and Canada. This compares to the 18,734 locations disclosed in a July regulatory filing.

Niccol has enjoyed the confidence of investors since taking over after his leadership at Chipotle Mexican Grill, where he is credited with leading a turnaround at the burrito chain.

“Starbucks is taking more aggressive actions within turnaround efforts. The store closures are more than we anticipated, while we believe the layoffs fit within management’s previously announced zero-based budgeting framework,” TD Cowen analyst Andrew Charles said.

Starbucks said on Thursday the job cuts would be in its support teams and added the company would also close many open positions.

|

|

|

Average CEO Pay is Growing and Fueling Economic Inequality

In 2024, CEO pay at S&P 500 companies increased 7% from the previous year—to an average of $18.9 million in total compensation.

The average CEO-to-worker pay ratio was 285-to-1 for S&P 500 Index companies in 2024. The median employee would have had to start working in 1740 to earn what the average CEO received in 2024.

|

|

|

|

|

Big news from California: four Blue Bottle cafés in the Bay Area just unionized with supermajority support at every location! Anti-union Nestlè owns the Blue Bottle chain, but Blue Bottle Independent Union has shown that they know how to fight back and WIN. The union already has six unionized locations in Boston–and now they need your support as they expand to the West coast, and beyond. What is voluntary recognition, you ask? Well, let’s get an explanation right from the U.S. Department of Labor: “Voluntary recognition is a way of respecting your employees’ choice to form a union and have collective bargaining representation based on a showing of majority support and without a formal election. While employers are generally not required to provide this recognition, a growing number of businesses are doing so. Voluntarily recognizing a union starts the collective bargaining relationship on a positive note. It streamlines the process for beginning negotiations on wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment.” So far, Blue Bottle has not lived up to its image as a progressive employer. The baristas in the Bay Area need a union to help them fight against the high cost of living, inconsistent staffing and scheduling, and lack of healthcare benefits they endure as baristas. The authoritarian work environment fostered by Blue Bottle leaves baristas without any voice in the workplace. One barista insisted that working conditions rapidly declined once Blue Bottle was acquired by Nestlè. “I have definitely seen a decline in the cafés, in our products, management, and barista morale. Short staffing, unprofessional management, and eliminating our bonuses have been consistent issues” said Alex Reyes, a barista with almost a decade at the company. In Solidarity, The Labor Force |

Avoiding the NLRB

The opening salvos of the second Trump administration have made clear that his administration aims to declare war on the labor movement and the working class. On January 28, President Trump fired two key National Labor Relations Board figures appointed by President Biden, Gwynne Wilcox and Jennifer Abruzzo. On February 19th, the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) evicted the NLRB’s Buffalo office and cancelled their 5-year lease with no warning. On March 27th, Trump issued an executive order ending collective bargaining for federal labor unions, and a federal appeals court upheld this order on May 19th. These actions likely presage a wider legal challenge to the existence of the National Labor Relations Board and, possibly, a wholesale repeal of the National Labor Relations Act.

The mainstream labor movement is either panicking or lining up to bend the knee to the new president. The NLRA underpins the legal existence, structure, and actions of virtually all unions in the United States. It is a key piece in the legal structure of labor relations, while the NLRB acts as a kind of referee between workers, unions, and employers. If the NLRA and NLRB disappear, the legal basis of most unions also evaporates, and the strategy of virtually all mainstream unionism is suddenly called into question. Much of the political left is also distraught about these developments after spending much of the past 4 years praising recent NLRB rulings as “progressive” elements of the Biden administration. If the legal basis of union organizing is removed, business unions will be confronted with an existential crisis that very few seem ready for: abandonment of legalistic, inside-baseball labor relations.

Of course, these developments raise several questions and observations about the business unions. The first is: what the hell did they expect? The NLRB is a body made up of presidential appointees who can be chosen and fired by the president more or less at will. As such, getting “good” people on the Board to make “favorable” rulings depends entirely on the electoral fortunes of a favored candidate or party (generally being the Democratic Party). Over the past 90 years of the NLRA, this has conditioned the labor movement into a meek, neutered shadow of what it once was; unions are now more likely to beg for scraps from the table of the political parties than to demand even the reformist position of a seat at the table.

It is a fantasy to assume, even if there are a few years when the government is slightly more friendly to unions, that this environment will last forever, particularly when the labor movement is historically weak and economic conditions are rapidly worsening for most workers. Functionally, this means that business unions can only campaign for Democrats during Republican administrations and can only organize or take action during Democratic administrations, while hoping that the Democrats will keep their promises, pretty please. And for what? Supposedly the “most pro-union President ever” Joe Biden himself intervened to stop major strikes several times during his term from 2021-2024, notably forcing a raw deal on railroaders just before Christmas in 2022 to avoid a disruptive strike and “protect the post-COVID economic recovery.” A Merry Christmas indeed.

Teamsters President Sean O’Brien drew widespread controversy in 2024 for cozying up with Trump, which, while reprehensible, only holds the mirror up to the AFL-CIO’s tight relationship to the Democrats, especially at a time when the Biden administration was actively collaborating with Israel’s genocidal Gaza campaign.

Ultimately, whether the mainstream unions cozy up to one party, the other, or both, the dynamic (and end result) is the same: insider horse trading in smoky rooms while workers’ power languishes, imperialist war tears apart families abroad, and deindustrialization continues at home. This is not a failure of political leadership on the part of unions; it is the inevitable result of the legal structure and class compromise of the NLRA. The entire point of the Act is to contain and destroy worker power over the economy, made explicit in its opening clause.

As many other IWW members have argued in the Industrial Worker and elsewhere so many times before, the solution to this problem is not to double down on ineffective bureaucratic methods. Invariably, these strategies (sectoral bargaining, state level joint labor councils, labor-management round tables, etc.) are motes of dust in the firestorm of modern global capitalism. They reproduce the mediocre parts of the NLRA at best and act as an obstacle to building democratic worker power at worst.

The only solutions available to us are direct worker power and class struggle. Capitalists and other ruling class goons will only give us what we want when we stop production and inflict economic pain on them; lawsuits and shame campaigns will never get major wins for workers in a period characterized by declining marginal profit rates and increasing elite capture of the regulatory and social welfare state. The effectiveness of bureaucratic strategies versus class struggle are evident at the large scale social and economic conditions today, but comparing two recent labor struggles with drastically different tactics and results underline the point more boldly.

The Starbucks Workers United campaign has relied since its beginnings in 2021 on the swift deployment of NLRB certification elections at individual cafes. A media air war has played out as SWU has tried to keep the ball rolling and reach a critical mass of the workforce to get a strong bargaining position for contract negotiations. Instead of using concerted direct action to force smaller wins and build up to larger concessions, SWU has relied on symbolic actions like corporate shaming, one-day “strikes” at select cafes, and so on. Contract bargaining has been stalled and dragged out for years with no real economic agreements reached and no end in sight. Starbucks, in 2024, won a Supreme Court case (Starbucks v. McKinney) challenging a fundamental part of NLRB’s legal basis. Several other major companies are conducting similar cases in an effort to undermine the NLRB framework. If this effort proves successful, SWU’s entire playbook – and indeed that of most of the labor movement – will be snatched and burned in front of them and years of time for thousands of members will have been wasted for nothing. I would argue, however, that it has already been wasted.

Contrast this with the 2024 Boeing Machinist strike. This struggle stands out in that the Boeing Machinists are historically very strike-ready and exercise that power within the extent possible under the NLRA. The workers walked off the job in September 2024 after a few years of agitating over declining working conditions, stagnant pay, safety, and poor quality products that spectacularly killed several hundred passengers in the previous decade. The all-out strike of about 40,000 workers paralyzed the company and ultimately cost management several billion dollars; the union accepted a tough compromise contract on a narrow approval margin after a few weeks on the line, with concessions including a 40 percent pay raise.

While the Boeing deal was not everything the workers wanted, it provides a sharp contrast to the strategy of avoiding real action by SWU. Had SWU spent 3-4 years preparing thousands of workers to strike for better pay and benefits like the Machinists, they would be in a far better position today to continue fighting struggles. But without any workers experienced in direct class struggle against the boss and a legal structure looking increasingly rickety, they are increasingly looking doomed. And from the point of view of this Wobbly, asking workers to put their jobs and livelihoods at risk for a project doomed from the start is political suicide. That is hundreds of thousands of hours of collective volunteer time from the membership, millions of dollars of dues, and god knows how much ink spilled into a black hole that members have not gotten much out of. At least the Machinists got to go home for the holiday break and buy their kids a nice Christmas present with a 40 percent pay bump. And a new generation of young Machinists see what they can do by stopping work.

Moving forward, instead of cultivating legal cases and lawyers, we must cultivate workers to organize, lead, and fight struggles directly against the employer. Instead of raising money to pay for an army of paid professional staff, we must be raising money to fight strikes and bail hardened union leaders out of jail. Instead of cultivating fellow workers to be petty bureaucrats filing grievances up the chain to lawyers and the NLRB, we must train them to be fighting workers who practice solidarity with all workers of the world by organizing direct class conflict.

It is the historic mission of the working class to take up the mantle of class struggle, seize the means of production, and establish a workers society free of the exploitation of capital. Those goals are lofty, but they can be accomplished only by the self-activity of workers exercising our power over the job. The bourgeoisie will fight us every single step of the way. It is time to stop pretending we can work with them and start building, relentlessly, the class struggle.

https://industrialworker.org/avoiding-the-nlrb/

|

Progressive Railroading / June 3rdBNSF Railway Co. yesterday announced it has created a new team focused on single carload growth. Led by General Director of Marketing Mark Ganaway, the First Mile/Last Mile team combines the Class I's short-line development and industrial products business development teams. It will be dedicated to growing carload volume across BNSF’s 32,500-mile network, according to a BNSF press release. “As our industry continues to evolve, every single carload is important to our network, and every single rail shipment helps our customers create more value for the nation’s consumer,” said BNSF Executive Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer Tom Williams. “First Mile/Last Mile will be focused on providing solutions and breaking down those barriers, leading to a more streamlined supply chain from start to finish.” |

To Unionize Amazon, Disrupt the Flow

This is an obvious claim to make in one sense, but what does it concretely mean today? There is nothing quite like a Chevrolet Plant No. 4 with tens of thousands of employees packed around it today. So how do we go after the big targets and disrupt their operations when the targets are more nimble, workplaces are fissured, and working-class communities are fractured and diffuse?

This article is an attempt to apply that one key lesson from the CIO period to the present. The big targets today are no longer manufacturing companies as they were at mid-century, but rather a mix of retail and parcel companies (see chart below), all of whose strength lies in the sophistication of their logistical operations — as Peter Olney has written, the other “historic basis of labor’s power.”

Just as it was apparent to CIO leaders that the labor movement was not playing to win if it did not take on GM and US Steel, so too is it increasingly clear that labor must go all in on organizing Amazon and Walmart today.

Amazon and Walmart are the biggest fish to fry, but most of the other large employers in the country, including FedEx, Home Depot, Target, Kroger, and Lowe’s, have built up their own highly efficient logistical capacities. If the biggest targets in the 1930s were all manufacturers, all of the key targets today are in logistics. But what kind of opportunity do contemporary logistics operations really pose for the labor movement?

Over 1,000 dairy worker Teamsters vote to authorize strike in Colorado, California, other states

Over 1,000 unionized dairy workers with the Dairy Farmers of America voted to authorize a strike amid what it called stalled contract negotiations in several states, including Colorado.

The workers who voted work at dairy processing and distribution centers in California, Colorado, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Utah. The Colorado locations include Henderson, Greeley, and Fort Morgan. The contract negotiations dealt with issues including pay, benefits, and workplace safety.

"Our demands are clear and simple: protect our work, respect our time, and pay us what we've earned," Lou Villalvazo, chairman of the Dairy Famers of America's National Bargaining Committee, said in a statement on Tuesday. "DFA can still avoid a strike, but time is running out. Our members are ready to walk."

The union says just one or two of these strikes could cause supply chain issues.

"We know how much money DFA makes, and we know what we deserve," said Peter Rosales, a Local 630 shop steward at Alta Dena Dairy in California. "This company is only successful because of us, and we take pride in our work. All we're asking for is our fair share."

Union officials went on to allege that Dairy Farmers of America was engaged in unfair labor practices.

https://www.cbsnews.com/colorado/news/over-1000-dairy-worker-teamsters-vote-authorize-strike-colorado-california/

Farmworkers in Sonoma County Win Settlement After Alleged Retaliation

Surrounded by elegant tasting rooms and high-end hotels, farmworkers and labor organizers rallied Wednesday in Healdsburg — the center of Sonoma County’s multimillion-dollar wine industry — to announce a settlement with Redwood Empire Vineyard Management, a Geyserville-based company.

“¿Tienen miedo? ¡No! ¿Están cansados! ¡No!” workers chanted in Spanish, which translates to “Are you afraid? No! Are you tired? No!”

REVM will pay $33,548 to seven former and current employees after the state’s Agricultural Labor Relations Board determined the company refused to offer them jobs because of their involvement in efforts to improve working conditions. The ALRB also found that REVM required farmworkers last year to sign a contract stating they would be immediately fired if they attempted to renegotiate their compensation.

According to state officials, the company’s actions are considered unfair labor practices in violation of California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

Sponsored

“We all have the right to be able to organize with our coworkers to ask for better working conditions and not be retaliated against,” said Yesenia De Luna, ALRB’s regional director. “In this case, workers were going to protests and marches asking for better wages. That’s a working condition.”

REVM did not return KQED’s multiple requests for comment.

Hillsboro students stage walkout after district announces ‘horrible’ cut to theater program at Century High School

by: Ariel Salk

Students in Hillsboro staged a walkout after the district announced cutting theater from next year’s curriculum at Century High School.

“The theater program is their career course. It’s what they want to do in their life, and they’re just ending it. It’s horrible,” said Century High School Senior Kenneth Polin.

The Hillsboro School District is facing a $20 million budget shortfall going into next year. A statement posted on the district’s website says they are projecting cutting nearly 150 positions. It said the reason for pulling the theater classes is that there are not enough students enrolled in theater.

“The reason is because not enough students forecasted for those electives. Even if all students who forecasted for Theater Foundations, Theater 2, Theater 3, Theater 4, Technical Theater 1, and Technical Theater 2 were combined, there would barely be enough students to justify one class — and having that many classes and levels in one class period would be impractical. Any elective, Career Pathway, or CTE course could be paused if numbers were that low, regardless of the budget situation,” said Hillsboro School District.

“It is what shapes people into being adults in their future lives. And it having less funding is directly against the shaping of the growing generation,” said Polin.

KOIN 6 News spoke with students who said their siblings and friends are very passionate about theater and they are upset with this announcement.

“Being able to act out and like perform for other people, that’s, I can’t even imagine losing that,” said Central High School Sophomore Ollie Rodman.

“It’s so easy to feel isolated amongst your peers, even when you’re sitting right next to them in their joking, you can feel alone. And if your program really helps students feel together and getting rid of it is stupid, it is beyond incompetent,” said Polin.

In addition to budget cuts, the district is projecting 100 fewer student next year at Century High School, meaning that school is laying off eight licensed positions and “not just their theater teacher,” the district said.

“The teachers are really nice here and miss the theater teacher. She’s amazing. I love her so much,” Rodman said.

“Principal Kasper is committed to continuing an after-school theater program at Century High School, which engages students who would have otherwise participated in the elective courses as well as any student interested in theater,” the district said.

Copyright 2025 Nexstar Media Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed

The Pitfalls of Collective Bargaining: Part I

The current cycle of major union contract negotiations has come to an end. For both the Teamsters and the United Auto Workers (UAW), this has been a critical year, a time when these unions would confront some of the largest and most profitable corporations in the world. UPS generated $74 billion dollars in profit in 2022, while General Motors profits were $21 billion dollars during the same year. The new, reform leadership of both unions pledged to organize militant struggles that would bring significant victories in wages and working conditions for their members. In their rhetoric, Teamsters President Sean O’Brien and UAW President Shawn Fain strongly suggested strikes would be used to extract the best deal possible for their members.

In the end, little actual pressure on the capitalists happened. The Teamster contract with the United Parcel Service (UPS), covering 340,000 workers, was settled without a strike, while the UAW agreement with the three large unionized auto corporations, covering 150,000 workers, was negotiated after a few weeks of token strikes.

The resulting contracts included some partial gains, but, overall, both sets of contracts fell far short of what had been promised. The Teamsters contract was approved by a large majority in a ratification vote, but union members nearly defeated the tentative contract at General Motors.

Groups like Teamsters Mobilize formed in opposition to their belief the Teamsters failed to live up to the radical promise presented this past summer. As rank and file workers mobilize to demand a more militant union, what are the lessons to be learned from this round of negotiations? Instead of going through each contract on a point-by-point basis, this article will seek to distill broader lessons to be learned from this most recent discouraging debacle. The focus will be looking at typical pitfalls that occur during the collective bargaining process, in the hope that they can be made to avoid themed in the future.

The Necessity for Militant Action

It was widely understood that both the UAW and the Teamsters had suffered from inept and corrupt leaders who had given away major concessions in previous contracts. Forcing the corporations to cancel these concessions would require a show of solidarity by union members. Yet little was done to prepare for a lengthy strike and contract negotiations proceeded smoothly with little sign of militant resistance.

Once the contract was negotiated, Teamster leaders insisted that the mere threat of a prolonged strike had been sufficient to extract significant concessions from UPS. This claim is empty bluster. Powerful corporations are not impressed by union threats. The only way to effectively counter corporate power is to shut down production for a lengthy period of time. Threats of militant action will be perceived as a bluff until the union can demonstrate that its members are united and willing to confront management.

A sizable strike fund makes it more possible to conduct a long strike. Such a fund cannot provide a total solution, but it can help. The UAW leadership turned this argument around by claiming that a full-scale strike at one of the large auto corporations would deplete the strike fund. This is upside down. Unions create strike funds so that they can conduct lengthy strikes.

The Need for Short-Term Contracts

Both the Teamsters and the UAW failed to organize militant strikes, so the contracts that were negotiated included a myriad of dubious provisions. To start, both contracts are for a time period that is far too long. The negotiation of a new contract is a crucial time when rank and file members can become actively involved in determining the union’s policies. Longer contracts allow union officials to entrench themselves in power as those on the shop floor become passive bystanders. The Teamsters contract will last for five years, while the UAW contract will extend for four and a half years. Both terminate in 2028. Just on this basis, both contracts should have been rejected. There is no valid reason for a union contract to last more than two years.

Wage Increases Versus Inflation

The need for contracts covering a short period of time becomes even more important in a period of rapid inflation. Predicting the rate of inflation for several years in the future is virtually impossible. Wars, breaks in the supply chain and the increasing volatility of global climate patterns can all trigger a spike in inflation.

A modest estimate of the inflation rate for the next five years would set it at five per cent (5%). The Teamster contract calls for an increase in the basic wage for full-time workers of 19% over the life of the contract. This would mean an increase of less than 4% per year. The chief financial officer of UPS estimated the total cost of the contract, wages and benefits, at 3.3% per year. These figures mean that union members will be receiving less in 2028 in total compensation, allowing for inflation, than they receive now.

The wage increases included in the UAW contract are marginally better. Full-time production workers will receive an increase of about 30% over the term of the contract, or an increase of about 6% per year. This includes expected increases due to a clause that provides partial protection against inflation.

Thus, the UAW contract will at least cover inflation, but not much more. Since 2008, when the union agreed to a contract filled with concessions, there has been a drop in real wages for union members of 19%. Just to get back to where its members were before, the UAW needed to negotiate a contract that would include pay increases substantially higher than the rate of inflation. The 2023 contract failed to do this.

Mollifying Skilled Workers

The current UAW leadership likes to congratulate itself as progressives pledged to a more just and equal society. Nevertheless, the current contract includes a provision that will significantly increase income disparities among full-time workers.

Skilled workers are an important segment of the auto industry workforce. Their votes are counted separately, although the final tally includes all union members. The UAW leadership knew that there would be significant opposition to the proposed contract among those working on the line, so they went out of their way to pacify the skilled trades.

In the first year of the contract, skilled workers will receive an additional $1.50 an hour, beyond the wage increases going to production workers. The special increase is termed a tool allowance. Over a year, this comes to $3000, a lot of tools.

This is a substantial increase, particularly since it is included for each year of the contract. Prior to the start of this contract, skilled workers received about $4.90 an hour more than full-time production workers. By 2028, this gap in pay will have increased to nearly $8.00 per hour. Over the life of the contract, the gap in pay between production workers and skilled workers will have increased by 65%. Instead of an egalitarian approach to wage rates, the UAW leadership opted for a strategy that increased wage differentials between skilled workers and those on the line.

The ploy worked. In General Motors, production workers in seven of the eleven large assembly plants rejected the proposed contract, but skilled workers overwhelmingly supported it by a margin of nearly two to one. In the end, the contract was narrowly approved, with 45% of UAW members at GM rejecting the contract. The leadership depended on the votes of skilled workers to carry a contract that held little appeal for many production workers.

This first section of the article looked at some of the broader issues raised by the UAW and Teamster contracts. The next section will look at specific points in the contracts.

Pitfalls in Collective Bargaining: Part 2

The first section of this article examined the broader issues raised by the recent Teamster and UAW contracts. Specifically, it looked at the length of the contracts and the wage increases granted to full-time workers. This second section will focus on some of the specific points in these contracts. As in the previous section, the intent is to recognize the pitfalls embedded in these contracts, in order to avoid these traps in the future.

Front Loading

Union leaders understood that the failure to substantially increase real wages over the life of the contracts would result in rank and file resistance to approving them. Those negotiating the contracts therefore turned to tricky maneuvers to overcome this resistance. One of these maneuvers was the front loading of wage increases.

When contracts are designed to last for several years, as both the Teamster and UAW contracts were, increases in the hourly wage rate can be scheduled so that the largest increases occur during the first year. Significantly lower increases are slotted for the following years, often significantly less than the expected inflation rate. The tentative contract can then be sold to the membership on the basis that ratification will lead to an immediate and rapid jump in wages. This is a tempting prospect for those living on the edge of financial disaster. Nevertheless, a few years later, with real wages falling, creditors will again be at the door and the cycle will begin again.

The UAW contract is a particularly flagrant example of front loading. Over the four and a half years of the contract, basic wages will rise by 25%. In the first year, wages will jump by 11%, before falling to 3% increases during the next three years. A provision in the contract provides a partial protection against inflation, so the total wage increase will come to 30% during the entire term of the contract. Of that, about 40% of the increase will come during the first year.

The Teamster contract with UPS is also front loaded. The basic wage rate will increase by $7.50 over the five years of the contract. Of this, $2.75 will come during the first year and an increase of only $4.75 an hour over the next four years, or about $1.20 on average each year. This means that UPS workers will get about 37% of their wage increase in the basic rate during the first year. Front loading is even worse when the entire package is taken into account. The chief financial officer of UPS has estimated that 46%, or nearly half, of the increase in total compensation, wages plus benefits, would be received during the first year of the contract. In a five year contract, this is front loading with a vengeance.

There is no legitimate reason for front loading a collective bargaining contract. Indeed, there is no reason for a lengthy contract in the first place. At least, when a lengthy contract is negotiated, wage and benefit increases should occur at a steady rate over the entire period covered. Front loading is designed to confuse union members and to convince them to accept an inadequate contract on the basis of an immediate, but short-lived, gain.

Bonus Payments

Another manipulative maneuver used to ensure ratification was the provision of a pay increase through a bonus payment. The UAW contract offered a $5000 bonus to full-time workers upon ratification. This is again tempting those in financial distress with an immediate but illusory solution to their problem.

Bonus payments are a one time event. Although the sum may seem a large amount, calculated over the entire length of the contract the amount is small. Furthermore, the bonus is not integrated into the basic wage rate. Thus, when the next contract is negotiated, the existing wage rate does not include the bonus payment. The starting point for the next contract is therefore likely to be a real wage, allowing for inflation, that is even lower than the one at the start of the current contract. Bonus payments are designed to confuse members. They should never be included in a contract.

The Tier System

Another set of problems involves the creation of artificial divisions, or tiers, within the workforce. The tier system is not only unjust, it is divisive.

The concessionary contracts negotiated by the previous administrations in both the UAW and the Teamsters were particularly harmful in that they created a tier system of pay categories. Union members doing exactly the same work, even those hired on a full-time basis, were being paid substantially different wages. These artificial divisions undermined solidarity within the union. The introduction of tiers was done deliberately by management with exactly this intent.

The UAW signed concessionary contracts for several decades prior to this last round of negotiations. In one of these previous contracts the UAW agreed to a special wage scale for new hires. Initially, a newly hired full-time production worker would receive a wage rate that was barely more than half the standard wage rate for production workers. The new hire would then receive small increases in pay for each year on the job. Only after eight years on the job would newly hired workers finally be merged into the regular pay scale and receive the wages due them given their seniority. The second tier for full-time workers remained in place during the contract that expired in 2023.

This provision in previous contracts proved to be enormously profitable for the auto corporations. The tier system fueled the opposition in the UAW and gave an impetus to the election of a new union leadership. Abolition of tiers was a key demand leading into the negotiations. Nevertheless, the new 2023 contract continues to include a second tier, although the number of years that new hires have to remain on this inferior scale before being moved on to the standard wage scale has been reduced from eight years to three years. Those workers who benefited from this change received a sizable increase and wages and provided much of the support for the new contract.

This provision of the new contract marks a significant improvement and yet the initial concession should never have been made. A truly militant union would start from a position of rejecting all previous concessions and build from there. Instead, the UAW settled for a limited, partial gain after a series of token strikes.

Part-Time Workers

In UPS, the primary division created by the contract is the huge gap between full-time and part-time workers. Nearly half the workforce is hired on a part-time basis. Under the previous Teamster contract, the wage rate for part-time workers was so low that many were being paid at the prevailing market rate for entry jobs. Part-time UPS workers were averaging $20 an hour in 2023 across the country, with the wage rate varying considerably by job market. Since the previous contract set the rate at less than $17, this meant that a majority of part-time UPS workers were being paid at the market rate, rather than a wage set through the collective bargaining process. Such a situation can only occur when a union totally fails its members.

The new, so-called reform Teamster leadership promised that they would fight for a contract that brought major gains to the part-time workers. They failed to do this. The new contract set the new rate for part-timers at $21 per hour. Although this is a substantial increase over the previous contract, it did little to help the majority of part-time workers employed at the prevailing market rate for their community. At the end of this contract, in 2028, the wage rate for part-timers will increase to $25.75. This modest increase might just keep up with inflation over the next five years. The Teamster contract with UPS is likely to leave current part-time employees with the same real wage in five years as they receive now.

Still, this is not the worst feature of the 2023 contract relating to the part-time workforce. Those hired following the start of the contract will be paid $21 an hour, but this will only increase to $23 by 2028. Part-time workers hired during the life of the contract will actually receive a lower real wage in five years than that received by part-time workers who were hired in 2023.

In effect, the new contract creates yet another tier of lower paid workers at UPS. There will now be full-time workers, part-time workers hired before the fall of 2023 and a third tier of part-time workers hired after 2023.

All part-time UPS workers should be placed on the same pay scale, no matter when they were hired. Even more important, the vast gap in pay between part-time and full-time workers should be eliminated. Every UPS worker should receive the same hourly wage rate and the same benefit package per hour, given their seniority, whether they are employed as full-time or part-time workers. The current Teamster leadership promised to end the tier system, but in fact the 2023 agreement creates a new tier of lower pay for part-time workers hired after the start of the contract.

Pensions

Cuts in pensions are one aspect of a major pitfall that is all too frequently included in collective bargaining agreements. In order to overcome rank and file resistance to inadequate contracts, concessions are included that have a detrimental impact on those who are excluded from the ratification vote. The UAW did this in the past by sharply lowering wages for those hired after the start of the new contract. The current Teamster leadership has followed the same path, but in relation to part-time workers rather than those hired on a full-time basis.

Retired workers receiving a pension are often the target of the same type of unscrupulous negotiating trick. UPS Teamster members are covered by twelve different pension funds, with specific benefits negotiated for each fund. The Teamster national master contract sets the amount that UPS pays to the relevant fund for each person covered. The contract froze this contribution for a majority of the pension funds for the next five years. These pension funds will remain solvent, so those who are eligible will continue to collect their pensions, and yet the amount they receive will not keep up with the rate of inflation. The 2023 contract will result in a significant decrease in the real value of the pensions received by a majority of Teamster UPS retirees.

A truly progressive union leadership would make sure that those least able to defend their interests are not negatively impacted by a new contract. The UAW and Teamster leaders failed to meet this basic standard and as a result, pensioners and part-time workers took a hit.

Air Conditioned Vans

To its credit, the Teamster leadership did make an effort to extend the usual scope of bargaining to meet the challenge set by the climate crisis. Summer heat waves are becoming more frequent and more intense. This has caused critical health problems for UPS drivers sweltering while delivering heavy packages in vans that absorb the sun’s rays. Indeed, several UPS van drivers have died of heat stroke. In July 2022, a driver in the Los Angeles area collapsed during a heat wave and could not be revived.

UPS management has recognized the problem but has done little to resolve it. The 2023 contract has been touted as a historical breakthrough since UPS has agreed to install air conditioning units in every van purchased after January 1, 2024. Unfortunately, the promise is better than the reality. UPS runs its delivery vans until they collapse. Apparently, it is cheaper to continue to repair a van than to buy a new one, so vans are often in use for more than twelve years. Given this, only one-third of the delivery vans being used by UPS in 2028, the final year of the current contract, will be equipped with air conditioning. By then, the summer heat will be significantly worse and a majority of UPS drivers will be even more stressed than now.

UPS makes billions of dollars in profit every year. A satisfactory agreement would have required management to have all UPS vans air conditioned by the end of the contract, either by buying new equipment or retrofitting old ones.

Conclusions

Triumphalism often characterizes the rhetoric of union officials as they seek to sell their members on a newly negotiated contract. Small gains become historic victories. Incomplete rollbacks of previously granted concessions become momentous breakthroughs. Partial advances improving the health and safety of the workforce become transformed into landmark successes.

It is not surprising that rank and file Teamster members or auto workers have become cynical about the new batch of supposedly progressive reform leaders. In reviewing the recent contracts, one is struck less by their major faults, although these are important, than by their overall mediocrity. There is no doubt that these are better contracts than those negotiated by Hoffa Junior or the incompetent and corrupt bureaucrats that occupied the UAW’s Solidarity House over the last two decades. Nevertheless, the Teamster and UAW contracts failed to deliver the genuine gains that would have significantly improved the wages, benefits, and working conditions of union members.

This raises the question: what type of changes need to be made before these unions can become truly militant forces for change?

Transforming Business Unions

The recent fiasco of the Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU) has raised the broader issue of how a business union can be transformed into a militant, class-conscious organization capable of defending the interests of its members.

From the start, the TDU project was flawed. In its earliest organizational form, the Teamster opposition caucus was called Teamsters for a Decent Contract. There can be no doubt that the contracts negotiated by Hoffa junior and his predecessors were horrendous. The sole creativity of the old Teamster leadership was the devising of new rationales for contract concessions. Still, their actions were not that different than those taken by the leaders of many other unions.

The globalization of capital has deliberately shifted the balance of class forces in the industrialized societies. The pragmatic response to this shift was a continuing series of concessions negotiated by union officials. In the Teamsters, the blatant corruption of the union leadership, along with the disastrous contracts, provided a fertile territory for a group of young radicals to leave graduate school and become truck drivers.

Nevertheless, framing the issue as one of organizing for a better contract was a fundamental strategic error. The only way to create a union that could effectively fight for a decent contract was to first radically alter the structure of the Teamsters. Merely electing a different set of bureaucrats as leaders within the existing union structure can not create a union that will actually challenge corporate power.

The Turn to the Working Class

In 1970, when the International Socialists (IS) adopted a “turn to the working class”, and sent some of its cadre to the Midwest to become truck drivers, a primary goal was to push the Teamsters Union into breaking with the two-party system. For socialists, independent political action has always been a basic tenet. The working class needs its own political party, so electoral activity should always be totally independent of both mainstream capitalist parties.

Thus, the irony of seeing the TDU be integrated into a new, “reform”, leadership that flirts with Trump and the Republican Party. Yet the recent turn of events in the United Auto Workers (UAW), where a reform caucus involving former members of IS has also been integrated into a newly elected leadership, has been only marginally different. The UAW remains embedded within the Democratic Party. For the IS members entering the working class, cutting the ties between most union leaders and the Democrats was a key step in reviving the unions. After all, there have been close ties between union bureaucrats and Democratic politicians since the Gompers era more than a century ago.

Breaking with the two capitalist parties remains a crucial prerequisite to a genuinely militant working class movement, but perhaps this should be viewed as part of a process. A union that engages in militant actions to defend the interests of its members will inevitably be the target of repressive actions by an administration controlled by Democrats. These conflicts will make it obvious that the Democratic Party represents the interests of a sizable section of the ruling class and not the interests of the working class. Once this is clearly understood, independent political action will be seen as the logical outcome. Nevertheless, the point needs to be made by socialists who are active within their unions.

A strategy that seeks to create a militant union by building an opposition caucus that can elect a new set of leaders is a strategy that is bound to fail. The focus of rank and file militants should always be on the creation of a democratic, decentralized union. The business union model has been designed to be coopted by management.

Toward A New Union Structure

An examination of the experiences of both the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the UAW in its formative years can provide some pointers for the structural transformation of existing unions. These proposed changes should not be taken as a rigid set of formulas, but rather a suggested direction.

One place to start is with the union’s leadership. Full-time officials, whether elected or staff, should never earn a wage that is higher than that received by the most highly paid category of workers within that union. Big Bill Haywood was paid a weekly wage as the general secretary-treasurer of the IWW that was in line with that being earned by copper miners. The current president of the Teamsters, Sean O’Brien, receives a salary of $250,000, more than three times the pay earned by a full-time driver at UPS on a regular shift.

Bureaucrats often argue that they need to be granted salaries similar to those being received by corporate managers. This is a telling sign of a business union. Highly paid union officials live in the same rarefied world as corporate executives. In a militant union, rank and file activists will be eager to serve as a full-time official for a time because they believe in its mission, and not because becoming a bureaucrat is viewed as an attractive career path.

Unions need to enforce a term limit on their officials. Election for office should be held frequently, with no more than two years between elections. There should also be a strict limit on the number of years one can hold any union office. A four-year time limit would seem a good starting point. This limit needs to hold over all full-time jobs, for both elected posts and staff jobs. Thus, someone could be elected to the national executive committee for two two-year terms, but at that point that individual would have to return to the shop floor, or leave the union.

Having union officials entrenched in office not only stifles the democratic process, it creates a climate that is resistant to new ideas and has difficulty in responding to new challenges. A continuing turnover in the union’s leadership at every level is essential for a vital, militant union.

One of the primary methods a union bureaucracy utilizes to create a machine is by filling staff jobs as patronage. The number of staff positions as organizer and grievance officer should be sharply limited. Furthermore, the hiring of staff jobs should be decentralized. Union locals, or perhaps metropolitan councils of locals, should be hiring staff, not the national leadership. Needless to say, the composition of union officials should reflect the diversity of the membership, both in terms of gender and ethnic minorities.

Limiting the number and compensation of full-time officials is an important way to shift power from the bureaucracy to the rank and file. Key to this process must be the development of a core of militants who can coordinate actions at the shop floor. These can be activists who do their regular jobs and then volunteer to represent their colleagues in their department to union members throughout that workplace. Ideally, a contract can be negotiated that provides for a representative from each unit within the workplace to be paid for union activity for a few hours a week.

The experience of Dodge Main is illustrative. Located in Hamtramck, Michigan, Dodge Main was an integrated complex made up of several automobile plants. Most of Chrysler’s cars were produced at Dodge Main in its heyday. As the UAW organized these plants during the late 1930s, it created a network of shop stewards. For every twenty-five workers, there was one steward representing the interests of union members against the demands of the foreman. Once the UAW was recognized as the bargaining agent, the shop stewards were embedded in the contract. Although they were paid their regular wage to conduct union business for several hours a week, they worked their regular jobs for most of their time in the plant. Each plant at Dodge Main had a shop steward’s council that brought together all of the stewards to resolve issues that impacted the entire workforce.

These days, most union members do not work in large, highly integrated workplaces. Nevertheless, a system of shop stewards is essential to the creation of a militant, democratic union. Perhaps there should be two delegates from each department, one for full-time workers and the other for part-time, precarious workers. Shop stewards from the entire workplace need to meet regularly to determine the union local’s overall direction. The shop steward’s council should also hold the responsibility for initiating actions concerning issues specific to that workplaces, issues such as safety and speed-up. These actions could vary from quick, short-term walkouts, slowdowns and work to rule to a full-scale strike of indefinite length.

Shifting power from full-time national union officials to rank and file activists and shop stewards is a critical element in a program to transform a business union, but questions concerning the negotiations of contracts are important as well. Often contracts are negotiated at the national level, such as the Teamster-UPS contract and the UAW contracts with the major auto corporations. Maintaining rank and file control over these negotiations is crucial to building a genuinely democratic union.

No contract should ever last for more than two years. Negotiations are a time when members can directly impact the union’s policies. The negotiating team should include several shop stewards and rank and file activists. They should be reporting regularly to members in their workplace on the current state of the talks. Transparency is key to democracy.

Once a tentative agreement on a contract has been reached a significant period, at least ten days, should occur before a vote. Members need time to fully understand a complex document before voting. Furthermore, both supporters and critics of the agreement should be given ample opportunity to explain their position to the membership. The ratification process should be viewed as a time when union members can gain a greater understanding of the problems confronting the union, It should not be a time when the leadership seeks to ram a proposed contract to an affirmative vote.

Conclusions

These are an outline of the drastic changes in structure and procedure that are required in order to transform a business union into a militant union willing to confront the corporate bosses. It is unlikely that the radical changes in structure that are required to transform a business union can be implemented within the existing organizational framework. Whether the formation of a new union is necessary or a reform movement is able to remain within the old structure is a question of lesser importance. The focus has to remain on the changes required to democratize the union by shifting power to the rank and file.

Finally, we need to state clearly that even a militant union can only win limited gains for its members within the narrowing constraints set by the globalization of capital. Only the revolutionary transformation of the capitalist system, and the creation of a democratic socialist society, can make it possible for the working class to achieve its goals.

Further Reading

Chester, Eric Thomas. The Wobblies in Their Heyday: The Rise and Destruction of the Industrial Workers of the World during the World War I Era. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2014; paperback ed., Amherst, MA: Levellers Press.

Jefferys, Steve. Management and Managed: Fifty Years of Crisis at Chrysler. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

La Botz, Dan. “Tumultuous Teamsters of the 1970s.” In Aaron Brenner, Robert Brenner and Cal Winslow, eds., Rebel Rank and File. Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2010.

Weir, Stan. Singlejack Solidarity. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1973.

© Copyright Labor Rising